2. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室 海洋渔业科学与食物产出过程功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266237;

3. 农业部海洋渔业可持续发展重点实验室, 山东省渔业资源与生态环境重点实验室, 中国水产科学研究院 黄海水产研究所, 山东 青岛 266071;

4. 上海海洋大学海洋科学学院, 上海 201306

2. Function Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China;

3. Key Laboratory of Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture; Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Fishery Resources and Ecological Environment, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China;

4. College of Marine Sciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China

渔业资源评估是渔业管理的基础[1], 数据有限性是现行渔业资源评估中常见的问题, 如渔获量或资源量指数的时间序列较短以及缺乏生长、死亡、补充等生活史信息, 这在一定程度上限制了一些资源评估模型的使用和评估效果[2]。因此, 数据有限性渔业资源评估方法的探索受到渔业科学家的广泛关注, 尤其是短生命周期的渔业种类[3]。短生命周期的渔业种类数据获取受限, 种群动态易受外界环境影响, 其资源评估面临着很多挑战[4-5]。头足类是典型的短生命周期的渔业种类, 用传统的资源评估模型难以准确描述其资源动态[6-11]。

消耗模型(depletion methods)[12]、年龄结构模型[13]、补充量的环境预测(environmental predictors of recruitment)[14]和剩余产量模型[15]等均被尝试用于头足类的渔业资源评估, 但前三者受数据限制[15], 而剩余产量模型只需要商业捕捞产量和捕捞努力量或单位捕捞努力量渔获量(catch per unit effort, CPUE)数据, 对缺乏年龄和个体大小信息的渔业种群仍能较好地评估其资源生物量和开发水平[16-21], 因此, 剩余产量模型成为应用最为广泛的模型[15]。然而, 由于剩余产量模型结构简单, 难以准确客观地反映种群结构、种间关系、补充、可捕性、环境条件等要素对资源动态的影响[22]。为此, 有关学者在模型中引入了过程误差和观测误差[23], 并且应用离散时间、状态空间、贝叶斯估计等方法提高了模型参数估计的精度[24-26]。Pedersen等[23]建立了连续时间的随机剩余产量模型(a stochastic surplus production model in continuous time, SPiCT), 该模型包括了捕捞量与生物量的观测误差, 也包括了种群动态的过程误差, 在评估数据有限的南大西洋长鳍金枪鱼资源时取得了较好的结果。但国内外尚未见到有关SpiCT模型应用于数据有限的短生命周期渔业种类资源评估的报道。

阿根廷滑柔鱼(Illex argentinus)为西南大西洋重要的头足类资源, 具有生命周期短、生长快、资源补充快的生物学特性[27-30], 数据获取有限, 不适合使用数据要求高的复杂模型。目前, 关于其资源评估或开发策略的研究较少, 涉及的模型主要包括Delury模型、基于贝叶斯的Schaefer模型和基于环境因子剩余产量模型[31-35]。因此, 本研究分析了6种参数设置方案下SPiCT对阿根廷滑柔鱼参数估计的变化及对其资源评估的影响, 以期为数据有限的短生命周期渔业种类的资源评估提供一个范例, 为渔业资源的适应性管理提供参考。

1 材料与方法 1.1 数据来源数据参考陆化杰等[33], 仅有捕捞产量和CPUE数据, 包括2001—2010年中国大陆、台湾省及福克兰群岛鱿鱼钓阿根廷滑柔鱼年捕捞产量统计数据及基于贝叶斯的广义线性模型(generalized linear Bayesian models, GLBM)标准化的CPUE数据, 使用贝叶斯方法对有限渔业数据进行优化。

1.2 SPiCT模型方法本研究采用Pedersen和Berg开发的SPiCT模型[23], 其基本公式如下:

| $ d{Z_t} = \left( {\frac{{\gamma m}}{K} - \frac{{\gamma m}}{K}{{\left[ {\frac{{{e^{{Z_t}}}}}{K}} \right]}^{n - 1}} - {F_t} - \frac{1}{2}\sigma _{\rm{B}}^2} \right)dt + {\sigma _{\rm{B}}}d{W_t} $ | (1) |

| $ \gamma = {n^{n/(n - 1)}}/(n - 1) $ | (2) |

| $ m = \frac{{\gamma K}}{{{n^{n/(n - 1)}}}} $ | (3) |

式中, Zt=ln(Bt); Bt为可利用种群生物量(exploitable stock biomass, ESB); Ft为捕捞死亡系数; K为容纳量; σB是过程噪声的标准差; Wt是布朗运动; n > 0是一个无单位参数, 决定产量曲线的形状。

阿根廷滑柔鱼的随机参考点(BMSY、FMSY和MSY)和预期平衡生物量(expected equilibrium biomass, EEB)公式如下:

| $ {{B}_{\rm{MSY}}}=B_{\rm{MSY}}^{\text{d}}\left( 1-\frac{1+F_{\rm{MSY}}^{d}{(n-2)}/{2}\;}{F_{\rm{MSY}}^{d}{{(2-F_{\rm{MSY}}^{d})}^{2}}}\sigma _{\rm{B}}^{2} \right) $ | (4) |

| $ {F_{\rm{MSY}}} = F_{\rm{MSY}}^d - \frac{{(1 - F_{\rm{MSY}}^d)(n - 1)}}{{{{(2 - F_{\rm{MSY}}^d)}^2}}}\sigma _{\rm{B}}^2 $ | (5) |

| $ {\rm{MSY}} = {\rm{MS}}{{\rm{Y}}^d}\left( {1 - \frac{{n/2}}{{1 - {{\left( {1 - F_{\rm{MSY}}^d} \right)}^2}}}\sigma _{\rm{B}}^2} \right) $ | (6) |

| $ \begin{array}{l} {\rm{EEB}} = E(\left. {{B_\infty }} \right|{F_t}) = K{\left( {1 - \frac{{(n - 1)}}{n}\frac{{{F_t}}}{{F_{\rm{MSY}}^d}}} \right)^{1/\left( {n - 1} \right)}} \times \\ \;\;\;\;\left( {1 - \frac{{n/2}}{{1 - {{\left( {1 - nF_{\rm{MSY}}^d + \left[ {n - 1} \right]{F_t}} \right)}^2}}}\sigma _{\rm{B}}^2} \right) \end{array} $ | (7) |

式中, MSYd=m代表了最大可持续产量,

SPiCT模型假定Ft由随机组分Gt和季节组分St构成, 公式如下:

| $ {F_t} = {S_t}{G_t} $ | (8) |

| $ d\ln {G_t} = {\sigma _{\rm{F}}}d{V_t} $ | (9) |

式中, dVt为标准布朗运动; σF为此噪声的标准差; 只能获得年度数据时, St=1。

连续时间下时间间隔Δt的渔获量可表示为下式:

| $ \ln \left( {{C_t}} \right) = \ln \left( {\int_t^{t + \Delta t} {{F_{\rm{S}}}{B_{\rm{S}}}dS} } \right) + { \in _t} $ | (10) |

式中, 渔获量观测误差

除了渔获量观测, SPiCT模型还假设有NobsI, i个可利用的生物量指标(It, i fori=1, …, Ni), 本研究中生物量指标为CPUE。公式如下:

| $ \ln \left( {{I_{t, i}}} \right) = \ln \left( {{q_i}{B_t}} \right) + {e_{t, i}} $ | (11) |

式中,

模型定义观测和过程误差的比率

本研究利用SPiCT模型拟合捕捞产量和CPUE数据, 通过比较阿根廷滑柔鱼2010年捕捞死亡系数F2010、生物量B2010与相应的生物学参考点FMSY、BMSY, 判断西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼在2010年资源状况。同时, 以2010年捕捞压力为基础, 预测2011年生物量B2011、预期平衡生物量EEB, 并将之与BMSY对比, 评估当前捕捞压力对阿根廷滑柔鱼资源量的预期影响。

1.3 阿根廷滑柔鱼模型参数方案设定Pedersen等[23]在SPiCT模型执行中构建了一个贝叶斯估计框架, 采用了在固定参数与无约束估计参数间折中的方式[37], 可使用概率分布的信息先验缩小目标模型参数的范围。

西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼冬季产卵群体数据包含NobsC=NobsI=10年的渔获量和CPUE, 这些信息不足以对参数α、β和n进行无约束估计, 因此, 应用模糊先验分布设定在ln域中α、β、n的平均值分别为1、1、2, 标准差为2。本研究提出6种参数设置方案(表 1)估计参数的后验分布, 拟合SPiCT模型。

|

|

表 1 连续时间的随机剩余产量模型(SPiCT)参数设置方案 Tab.1 Scenarios for different parameters settings of a stochastic surplus production model in continuous time (SPiCT) |

方案1参照Pedersen等[23]对南大西洋长鳍金枪鱼的资源拟合, 只对α、β和n进行先验分布设定; 方案2在方案1的基础上, 加入了模型参数环境容量K、内禀增长率r的先验对数正态分布, 参考陆化杰等[33]的研究, K、r分布在ln域中分别设定为lnK~N[ln150, 0.52]、lnr~N(ln1, 0.22); 方案3在方案2的基础上, 根据汪金涛[34]的研究结果, 设定lnq~N[ln0.23e-05, (3e-1)2], 方案4设定lnq~ N[ln0.40e-05, (3e-1)2]; 方案5在方案2的基础上, 对生物量的初始值设定先验分布, 考虑到其他学者[33-34]的研究结果, 设定2001年生物量B2001在ln域中服从lnB2001~N(ln150, 0.022); 方案6综合方案4和方案5的设定, 在方案2的基础上, 设定lnq~N(ln0.40e-05, (3e-1)2)、lnB2001~N(ln150, 0.022)。各种参数设置方案所得估计量与基于贝叶斯Schaefer模型[33](用S表示)、基于索饵环境因子的剩余产量模型和基于综合环境因子(产卵+索饵)的剩余产量模型[34](分别用F-EDSP和S-F- EDSP表示)所得估计量对比, 综合分析SPiCT模型在数据有限的情况下对评估阿根廷滑柔鱼的评估效果。

1.4 模型执行与校验用One-Step-Ahead(OSA)残差对模型拟合质量进行评价[38], 用Ljung-Box检验[39]检测模型是否违反独立性假设, 用Shapiro-Wilk检验[40]检测残差的正态性。

分别计算6种方案下产量、CPUE估计值和观测值的最小残差平方和(the sum of squares residuals, SSR)以评价各个方案拟合优度, 计算公式为:

| $ {\rm{SSR}} = \sum\limits_{t = 2001}^{t = 2010} {{{\left( {{x_t} - {{\hat x}_t}} \right)}^2}} $ | (12) |

式中, xt为产量或CPUE观测值,

模型实现由R软件中的程序包TMB[41](Template Model Builder)和SPiCT[23]完成。其中使用欧拉方案[42]解决连续时间模型的时间维度问题, 每年时间区间的数量为1/dtEuler。时间步长(dtEuler)越小越精确地近似于连续时间, Pedersen等[23]研究证实, 通常情况下, dtEuler =1/16评估效果均不错。考虑到阿根廷滑柔鱼生命周期不超过18个月, 生长速率较快[43-46], 本研究设定dtEuler=1/64。程序包SPiCT包含贝叶斯估计、模型拟合和模型校验程序, 其使用方法可在Pedersen等[23]文章支持信息Data S2中查到, 本研究不再详述。

2 结果与分析方案1只对α、β和n进行先验分布设定, 而拟合的结果出现了与生物学不符的情况, r为42.2, 最大可持续产量MSY(201.66×104 t)大于环境负载容量K(19.11×104 t)和BMSY(9.56×104 t), 方案1不可接纳(表 2)。方案2~6中, α、β和n的后验估计值较先验发生了很大变化(表 2), 模型校验结果显示, 5种方案P值相近, 均无显著违反模型有关独立性、偏差和正态分布性的假设(表 3、表 4)。

|

|

表 2 连续时间的随机剩余产量模型(SPiCT)参数估计值与其他模型参数估计值对比 Tab.2 Comparison of estimated parameters using a stochastic surplus production model in continuous time (SPiCT) and other models |

|

|

表 3 连续时间的随机剩余产量模型(SPiCT)渔获量残差诊断和模型校验 Tab.3 Diagnostics and checking of catch residuals obtained by a stochastic surplus production model in continuous time (SPiCT) |

|

|

表 4 连续时间的随机剩余产量模型(SPiCT)CPUE残差诊断和模型校验 Tab.4 Diagnostics and checking of CPUE residuals obtained by a stochastic surplus production model in continuous time (SPiCT) |

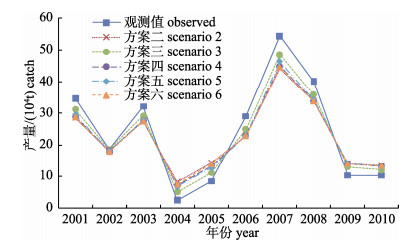

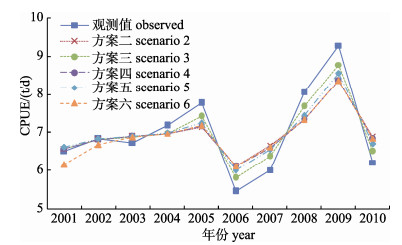

方案2~6中β、FMSY、F2010、preF2011、preC2011值随q值增大呈现上升趋势, n、K、BMSY、MSY、B2010、preB2011和EEB值随q值增大呈现下降趋势(表 2)。相比其他方案, 方案3阿根廷滑柔鱼2001—2010年产量和CPUE的估计值更接近观测值(图 1、图 2)。不同方案残差平方和(表 3、表 4)显示, 方案3估计的产量、CPUE残差平方和最小, 分别为114.23、0.93, 因此, 本研究确定方案3为阿根廷滑柔鱼资源评估的最适方案。

|

图 1 西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼历年产量与不同参数设置方案下SPiCT模型的估计产量拟合图 Fig.1 Observed and estimated catch of Illex argentinus in the southwest Atlantic Ocean from SPiCT under different scenarios |

|

图 2 西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼历年CPUE与不同参数设置方案下SPiCT模型的估计CPUE拟合图 Fig.2 Observed and estimated CPUE of Illex argentinus in the southwest Atlantic Ocean from SPiCT under different scenarios |

方案3(表 2)显示阿根廷滑柔鱼2010年捕捞死亡系数F2010为0.07, 小于FMSY(0.70), MSY为63.17x104 t, 而实际产量仅为10.23×104 t。另外, B2010(251.12×104 t)、以2010年捕捞压力为基础预测的2011年生物量preB2011(251.97×104 t)和预期平衡生物量EEB(252.42×104 t)均大于BMSY(118.51× 104 t), 这表明西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼在2010年资源状况良好。

3 讨论SPiCT模型的输入数据仅有时间序列的渔获量和生物量指标(如CPUE), 由于数据的有限性, 先验信息的设定影响了模型拟合的结果。在阿根廷滑柔鱼资源评估中, 仅凭α、β和n的先验设定, 拟合出的结果与观测值有一定差距(表 2), 而且α、β所代表的过程和观测变异参数σB、σB、σI, i和σC估计所用数据的获得比较困难。由表 2可知, K、r、Bt、q、F模糊或信息先验分布或数值固定很大程度影响了模型的拟合结果, 从残差平方和(表 3、表 4)可知, 方案5估计的产量和CPUE残差平方和都小于方案2, 其原因是B2001的先验设定对模型拟合产生了影响, 而实际中确定Bt信息先验或固定精确数值难度较大。对比方案2、3和4的估计结果发现, 可捕系数q的估算在很大程度上影响到了SPiCT模型K、B值的估计(表 2), 所以q的估算和选择显得尤为重要, 优化估计q以提升模型结果的准确性和精确性需要进一步研究。通过声学[47-48]估算的绝对生物量B, 以及结合公式C=qB求得的q值可分别作为设置Bt、q的先验分布的重要依据。

SPiCT和F-EDSP、S-F-EDSP均为以剩余产量模型为基础的状态空间模型, SPiCT模型综合考虑了环境因子、种间相互作用和网具选择性等因素引发的观测和过程误差, 而F-EDSP、S-F- EDSP分别是基于索饵场环境因子的剩余产量模型和基于综合环境因子(产卵场环境因子+索饵场环境因子)的剩余产量模型[34]。方案3下的SPiCT模型与S-F-EDSP模型对阿根廷滑柔鱼B2010和MSY的估计结果非常相近(表 2)。Chang等[49]根据台湾船队的阿根廷滑柔鱼产量, 使用地统计方法研究发现2007年后生物量开始大幅下降, 2007年中国大陆、台湾省及福克兰群岛鱿鱼钓阿根廷滑柔鱼年捕捞产量为54.55x104 t, 考虑到其他未统计产量及环境变化因素, 本研究认为MSY在58x104~63.17x104 t范围内较为合理, 即方案3下的SPiCT模型与S-F-EDSP模型估计的MSY较为合理, 而S模型和F-EDSP模型估计的MSY过高(表 2)。

不同的是, 方案3先验设置下的SPiCT模型对阿根廷滑柔鱼参考点K、BMSY和r (分别为270x 104 t、118.51x104 t和1.03)的估计结果与S-F- EDSP(分别为350x104 t、174x104 t和0.66)存在较大差异(表 2)。产生较大差异的原因除了SPiCT模型和S-F-EDSP模型的模型基础(S-F-EDSP模型是在Schaefer模型基础上构建的环境因子剩余产量模型)不同外, 可能与模型考虑生物与环境等因素及误差有关。SPiCT模型和S-F-EDSP模型均采用了贝叶斯估计, 而S-F-EDSP模型在考虑索饵场环境因子的基础上着重考虑了产卵期间产卵场的SST等因素, 未考虑资源动态受种群结构、种间作用、补充、可捕性等要素及采样误差的影响, 这可能是造成SPiCT模型和S-F-EDSP模型参数估计存在较大差异的原因之一。这两个模型的资源评估结果均表明阿根廷滑柔鱼的资源量处于较好的水平, 与其他学者研究结果[50]基本一致。大多数产量模型脱离了捕捞过程, 如离散模型假设Ft=Ct/Bt, 并且假设观测到渔获量没有误差[24, 26], 实际上渔获量存在观测误差, 可直接传递给Ft进而影响当前捕捞压力得出的结论。本研究中SPiCT模型作为时间连续模型通过方程(8)把Ft作为一个单独未被观测的过程, 可使Ft的计算在缺少渔获量的情况下变得可能[23]。这个过程解决了离散模型假设渔获量没有观测误差的缺陷, 使得SPiCT模型在一定程度上优于离散模型。大多数产量模型估计过程和观测误差是极其困难的[51-52], 针对这一问题, 本研究通过贝叶斯方法估计了过程误差与观测误差的比率(α、β), 简化了产量模型估计过程和观测误差的计算方法。阿根廷滑柔鱼补充量受海表温度等环境因子影响较大[53-54], 各年份季节环境因子变化大, 资源动态随季节发生变化, 阿根廷滑柔鱼与其他渔业种类相比, 更适于包含生物量、资源动态和渔获量、生物量指标(CPUE)的观测误差的SPiCT模型。此外, SPiCT模型较S-F-EDSP模型数据要求低, 计算方法简单, 综合考虑过程和观测误差, 本研究认为SPiCT模型相比S、F-EDSP、S-F-EDSP模型等连续模型及其他离散模型更适合数据有限、短生命周期的阿根廷滑柔鱼的资源评估。

SPiCT模型是对种群动态过程的简化, 尽管本研究中残差通过了所有测试(表 3、表 4), 但其预测结果具有不确定性, 不应依赖其产生长期预测(>2年), 因此, 本研究未进行不同管理方案下资源的长期预测分析。SPiCT模型长期预测的不确定性对其在数据有限、短生命周期的阿根廷滑柔鱼资源评估的影响及减少不确定性方面需要进一步研究。

| [1] |

Guan W J, Tian S Q, Zhu J F, et al. A review of fisheries stock assessment models[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2013, 20(5): 1112-1120. [官文江, 田思泉, 朱江峰, 等. 渔业资源评估模型的研究现状与展望[J]. 中国水产科学, 2013, 20(5): 1112-1120.] |

| [2] |

ICES Advisory Committee. ICES implementation of advice for data-limited stocks in 2012 in its 2012 advice[R]. 2012, ICES CM 2012/ACOM 68. 42.

|

| [3] |

Punt A E, Huang T C, Maunder M N. Review of integrated size-structured models for stock assessment of hard-to-age crustacean and mollusc species[J]. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2013, 70(1): 16-33. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fss185 |

| [4] |

Alemany J, Foucher E, Vigneau J, et al. Stock assessment models for short-lived species in data-limited situations: case study of the English Channel stock of cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis)[R]. Anchorage, Alaska: 30th Lowell Wakefield Symposium: Tools and Strategies for Assessment and Management of Data-Limited Fish Stocks, 2015.

|

| [5] |

Challier L, Royer J, Robin J P. Variability in age-at-recruitment and early growth in English Channel Sepia officinalis described with statolith analysis[J]. Aquatic Living Resources, 2002, 15(5): 303-311. DOI:10.1016/S0990-7440(02)01184-1 |

| [6] |

Caddy J F. Advances in assessment of world cephalopod resources[J]. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 1983, 231: 469. |

| [7] |

Roper C F E, Sweeney M J, Nauen C E. Cephalopods of the world: an annotated and illustrated catalogue of species of interest to fisheries[J]. FAO Fisheries Synopsis, 1984, 3(125): 47-49. |

| [8] |

Boyle P, Rodhouse P. Cephalopods: Ecology and Fisheries[M]. New York: John Wiley, 2005: 464.

|

| [9] |

Royer J, Pierce G J, Foucher E, et al. The English Channel stock of Sepia officinalis: Modelling variability in abundance and impact of the fishery[J]. Fisheries Research, 2006, 78(1): 96-106. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2005.12.004 |

| [10] |

ICES. Report of the Working Group on Cephalopod Fisheries and Life History (WGCEPH)[R]. Lisbon: 28 February-03 March 2011, Lisbon. ICES Document CM 2011/SSGEF: 03.

|

| [11] |

ICES. Report of the Working Group on Cephalopod Fisheries and Life History (WGCEPH)[R]. 27-30 March 2012, Cadiz. ICES Document CM 2012/SSGEF: 04.

|

| [12] |

Pierce G J, Allcock L, Bruno I, et al. Cephalopod biology and fisheries in Europe[J]. ICES Cooperative Research Report, 2010(303): 175. |

| [13] |

Royer J, Périès P, Robin J P. Stock assessments of English channel loliginid squids: updated depletion methods and new analytical methods[J]. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2002, 59(3): 445-457. DOI:10.1006/jmsc.2002.1203 |

| [14] |

Zuur A F, Pierce G J. Common trends in northeast Atlantic squid time series[J]. Journal of Sea Research, 2004, 52(1): 57-72. DOI:10.1016/j.seares.2003.08.008 |

| [15] |

Gras M, Roel B A, Coppin F, et al. A two-stage biomass model to assess the English Channel cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis L.) stock[J]. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2014, 71(9): 2457-2468. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsu081 |

| [16] |

Punt A E. Extending production models to include process error in the population dynamics[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 2011, 60(10): 1217-1228. |

| [17] |

Polacheck T, Hilborn R, Punt A E. Fitting surplus production models: Comparing methods and measuring uncertainty[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 1993, 50(12): 2597-2607. |

| [18] |

Zhang Z. Evaluation of logistic surplus production model through simulations[J]. Fisheries Research, 2013, 140: 36-45. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2012.12.003 |

| [19] |

Ichii T, Mahapatra K, Okamura H, et al. Stock assessment of the autumn cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the North Pacific based on past large-scale high seas driftnet fishery data[J]. Fisheries Research, 2006, 78(2-3): 286-297. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2006.01.003 |

| [20] |

Ludwig D, Walters C J. Are age-structured models appropriate for catch-effort data?[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 2011, 42(6): 1066-1072. |

| [21] |

Roel B A, Butterworth D S. Assessment of the South African chokka squid Loligo vulgaris reynaudii: Is disturbance of aggregations by the recent jig fishery having a negative impact on recruitment?[J]. Fisheries Research, 2000, 48(3): 213-228. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(00)00186-7 |

| [22] |

Pella J J, Tomlinson P K. A generalized stock production model[J]. Bulletin of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, 1969, 13(5): 421-458. |

| [23] |

Pedersen M W, Berg C W. A stochastic surplus production model in continuous time[J]. Fish and Fisheries, 2016, 18(2): 226-243. |

| [24] |

Meyer R, Millar R B. BUGS in Bayesian stock assessments[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 1998, 56(6): 1078-1087. |

| [25] |

Schnute J. Improved estimates from the Schaefer production model: theoretical considerations[J]. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1977, 34(5): 583-603. DOI:10.1139/f77-094 |

| [26] |

Ono K, Punt A E, Rivot E. Model performance analysis for Bayesian biomass dynamics models using bias, precision and reliability metrics[J]. Fisheries Research, 2012, 125-126: 173-183. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2012.02.022 |

| [27] |

Arkhipkin A I. Squid as nutrient vectors linking Southwest Atlantic marine ecosystems[J]. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2013, 95: 7-20. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2012.07.003 |

| [28] |

Lu H J, Chen X J, Cao J. CPUE Standardization of Illex argentinus for Chinese Mainland squid-jigging fishery based on generalized linear Bayesian models[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2013, 33(17): 5375-5384. [陆化杰, 陈新军, 曹杰. 基于GLBM模型:中国大陆阿根廷滑柔鱼鱿钓渔业CPUE标准化[J]. 生态学报, 2013, 33(17): 5375-5384.] |

| [29] |

Chen C S, Chiu T S. Standardising the CPUE for the Illex argentinus fishery in the Southwest Atlantic[J]. Fisheries Science, 2009, 75(2): 265-272. DOI:10.1007/s12562-008-0037-1 |

| [30] |

Waluda C M, Trathan P N, Rodhouse P G. Influence of oceanographic variability on recruitment in the Illex argentinus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) fishery in the South Atlantic[J]. International Journal of Peptide & Protein Research, 1999, 183(1): 159-167. |

| [31] |

FAO. Report of the ad hoc working group on fishery resources of the patagonian shelf[R]. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organizations, 1983: 83.

|

| [32] |

Basson M, Beddington J R, Crombie J A, et al. Assessment and management techniques for migratory annual squid stocks: the Illex argentinu, fishery in the Southwest Atlantic as an example[J]. Fisheries Research, 1996, 28(1): 3-27. DOI:10.1016/0165-7836(96)00481-X |

| [33] |

Lu H J, Chen X J, Li G, et al. Stock assessment and management for Illex argentinus in Southwest Atlantic Ocean based on Bayesian Schaefer model[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2013, 24(7): 2007-2014. [陆化杰, 陈新军, 李纲, 等. 基于贝叶斯Schaefer模型的阿根廷滑柔鱼资源评估与管理[J]. 应用生态学报, 2013, 24(7): 2007-2014.] |

| [34] |

Wang J S. Fishery forecasting and stock assessment for commercial oceanic ommastrephid squid[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ocean University, 2015. [汪金涛.大洋性经济柔鱼类渔情预报与资源量评估研究[D].上海: 上海海洋大学, 2015.] http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10264-1015974866.htm

|

| [35] |

Han Q P, Ding Q, Chen X J. Optimizing allocation on exploitation of Illex argentinus in the Southwest Atlantic[J]. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 2016, 25(2): 263-270. [韩青鹏, 丁琪, 陈新军. 西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼资源开发策略研究[J]. 上海海洋大学学报, 2016, 25(2): 263-270.] |

| [36] |

Thorson J T, Minto C, Minte-Vera C V, et al. A new role for effort dynamics in the theory of harvested populations and data-poor stock assessment[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 2013, 70(12): 1829-1844. |

| [37] |

Magnusson A, Hilborn R. What makes fisheries data informative?[J]. Fish and Fisheries, 2007, 8(4): 337-358. DOI:10.1111/faf.2007.8.issue-4 |

| [38] |

Harvey A C. Foercasting, Structural Time Series Models and the Kalman Filter[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

|

| [39] |

Ljung G M, Box G E P. On a measure of lack of fit in time series models[J]. Biometrika, 1978, 65(2): 297-303. DOI:10.1093/biomet/65.2.297 |

| [40] |

Shapiro S S, Wilk M B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples)[J]. Biometrika, 1965, 52(3-4): 591-611. DOI:10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591 |

| [41] |

Kristensen K, Nielsen A, Berg C W, et al. TMB: Automatic differentiation and laplace approximation[J]. Journal of Statistical Software, 2015, 70(5): 1-21. |

| [42] |

Basov S. Simulation and inference for stochastic differential equations: With R examples[J]. Economic Record, 2010, 86(272): 137-140. DOI:10.1111/ecor.2010.86.issue-272 |

| [43] |

Koronkiewicz A. Growth and life cycle of squid Illex argentinus from Patagonian and Falkland Shelf and Polish fishery of squid for this region: 1978-1985[R]. ICES C.M./K, 1986, 27: 25.

|

| [44] |

Sakai M, Brunetti N, Ivanovic M, et al. Interpretation of statolith microstructure in reared hatchling paralarvae of the squid Illex argentinus[J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2004, 55(4): 403-413. DOI:10.1071/MF03148 |

| [45] |

Arkhipkin A. Age, growth, stock structure and migratory rate of pre-spawning short-finned squid Illex argentinus based on statolith ageing investigations[J]. Fisheries Research, 1993, 16(4): 313-338. DOI:10.1016/0165-7836(93)90144-V |

| [46] |

Lu H J, Chen X J. Age, growth and population structure of Illex argentinus based on statolith microstructure in Southwest Atlantic Ocean[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2012, 36(7): 1049-1056. [陆化杰, 陈新军. 利用耳石微结构研究西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼的日龄、生长与种群结构[J]. 水产学报, 2012, 36(7): 1049-1056.] |

| [47] |

Zhang J, Jiang Y E, Chen Z Z, et al. Preliminary study on the nautical area scattering coefficient and distribution of mesopelagic fish species in the central-southern part of the South China Sea[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2017, 24(1): 120-135. [张俊, 江艳娥, 陈作志, 等. 南海中南部中层鱼资源声学积分值及时空分布初探[J]. 中国水产科学, 2017, 24(1): 120-135.] |

| [48] |

Zhang J, Chen B G, Zhang P, et al. Estimation of purpleback flying squid (Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis) resource in the central and southern South China Sea based on fisheries acoustics and light-falling net[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2014, 21(4): 822-831. [张俊, 陈国宝, 张鹏, 等. 基于渔业声学和灯光罩网的南海中南部鸢乌贼资源评估[J]. 中国水产科学, 2014, 21(4): 822-831.] |

| [49] |

Chang K Y, Chen C S, Chiu T Y, et al. Argentine shortfin squid (Illex argentinus) stock assessment in the southwest Atlantic using geostatistical techniques[J]. Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, 2016, 27(2): 281. DOI:10.3319/TAO.2015.11.05.01(Oc) |

| [50] |

Lu H J. Fishery biology and stock assessment for Illex argentines squid in the southwest Atlantic Ocean[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ocean University, 2012. [陆化杰.西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼渔业生物学及资源评估[D].上海: 上海海洋大学, 2012.]

|

| [51] |

Valpine P D, Hilborn R. State-space likelihoods for nonlinear fisheries time-series[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 2005, 62(9): 1937-1952. |

| [52] |

Polacheck T, Hilborn R, Punt A E. Fitting surplus production models: comparing methods and measuring uncertainty[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 1993, 50(12): 2597-2607. |

| [53] |

Liu B L, Chen X J. Preliminary study on the relationship between the distribution of production of Illex argentinus and SST in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean in 2001[J]. Marine Fisheries, 2004, 26(4): 326-330. [刘必林, 陈新军. 2001年西南大西洋阿根廷滑柔鱼产量分布与表温关系的初步研究[J]. 海洋渔业, 2004, 26(4): 326-330. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-2490.2004.04.016] |

| [54] |

Boyle P R. Cephalopod biology in the fisheries context[J]. Fisheries Research, 1990, 8(4): 303-321. DOI:10.1016/0165-7836(90)90001-C |

2018, Vol. 25

2018, Vol. 25