基于对海洋无脊椎动物免疫学、细胞生物学、发育生物学以及遗传育种学等方面研究的需要, 海洋无脊椎动物细胞培养备受关注。然而, 由于缺乏必要的基础生物学研究背景, 以及海洋无脊椎动物的特殊性, 其细胞培养难度较大, 迄今未见相关细胞系建立的报道[1-2]。因此, 建立稳定的原代培养细胞将在一定程度上弥补当前的研究需求。

海洋双壳类具有较高的经济价值, 是中国海水养殖业的重要组成部分。目前, 已报道了牡蛎、贻贝、文蛤等十几个物种的多种组织细胞的体外培养研究, 大部分为原代培养[3]。贝类的心脏组织细胞容易获取和解离, 并保持高活力, 同时微生物污染程度低, 因此常被用于体外细胞培养的研究[1, 4-9]。Hanana等[10]报道, 沟纹蛤仔(Ruditapes decussatus)心脏细胞可在含有20% L-15培养基和10%胎牛血清(fetal bovine serum, FBS)的海水培养基中存活1个月, 该原代培养体系中的细胞包含三类细胞, 即:上皮样细胞、圆形细胞和成纤维细胞。在太平洋牡蛎(Crassostrea gigas)心脏细胞培养中, Deuff等[11]在L-15培养基中添加了10% FBS, 可维持心肌细胞体外存活10~15 d, 原代培养物中以心肌细胞为主要细胞类型, 另外还有成纤维细胞、色素细胞以及少量的血淋巴细胞; Pennec等[12]在添加了10% FBS的L-15培养基中体外培养太平洋牡蛎心脏细胞, 使其存活2个月, 同时观察到细胞的“跳动”。Le Marrec-Croq等[13]在添加了10% L-15和10% FBS的无菌海水中培养欧洲扇贝(Pecten maximus)的心脏细胞, 该原代细胞在体外存活达1个月之久。

栉孔扇贝(Chlamys farreri)作为中国重要的经济贝类, 有关其体外培养的研究目前在幼虫、外套膜、精巢中有相关报道[14-16]。本研究采用植块法启动栉孔扇贝心脏细胞的原代培养, 通过基础培养基筛选和添加因子优化, 获得一个可使扇贝心脏细胞长期存活的培养基并建立了稳定的原代培养体系, 为扇贝基础生物学、病原体侵染机制和功能基因的研究搭建平台。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料栉孔扇贝购自青岛市台东海得发海鲜市场, 壳高3~4 cm。选择健康个体, 去除附着物、刷净壳表面, 75%酒精消毒壳表面后, 置于无菌过滤海水(添加青霉素100 IU/mL, 链霉素100 μg/mL, 制霉菌素1 μg/mL)中充气暂养24 h以上, 暂养密度为4个/L, 水温15℃。

1.2 基础培养基及添加物M199培养基、L-15培养基均为Gibco公司产品; 胎牛血清(FBS)为Hyclone公司产品; 牛磺酸为Sigma公司产品; 实验中所有其他化学试剂均为分析纯。

参考Gong等[17]的报道, 本实验向基础培养基中添加无机盐(NaCl 20.2 g/L、KCl 0.54 g/L、MgSO4 1 g/L、MgCl2 3.9 g/L), 使其渗透压达到1100 mOsm/kg。

1.3 培养条件优化 1.3.1 基础培养基筛选实验设计3种基础培养基(L-15、M199、L-15+M199), FBS浓度固定为10%, 每组设2个平行样, 实验重复2次。以组织块迁出细胞数量、细胞存活时间作为评价指标。

1.3.2 添加物浓度筛选根据预实验, 选定FBS、牛磺酸和Ca2+为添加因子, 实验设计3个FBS浓度(5%、10%、20%)、3个牛磺酸浓度(5 mmol/L、20 mmol/L、50 mmol/L)和3个Ca2+浓度(2 mmol/L、4 mmol/L、6 mmol/L), 采用L9(34)正交实验形成9个实验组(表 1), 每组设2个平行样, 实验重复2次。以细胞迁出距离、细胞存活时间作为评价指标。每组随机选择6个视野拍照, 使用Photoshop软件测量细胞迁出距离; 使用台盼蓝染色的方法鉴定细胞的存活。

|

|

表 1 正交实验中各实验组的添加因子浓度 Tab.1 The added factor concentration of each group in orthogonal design |

取样前先用75%酒精棉球擦拭壳表面, 超净台中无菌切断闭壳肌打开贝壳, 于围心腔内取出心脏组织。参考郎刚华等[14]的方法, 将其先于高压灭菌过滤海水中清洗2~3遍, 移入组织消毒液(高压灭菌的过滤海水中添加抗生素:青霉素500 IU/mL、链霉素500 μg/mL、庆大霉素100 IU/mL、制霉菌素2 μg/mL)中浸泡20 min, 在无菌过滤海水中清洗组织3~5次。将组织块移至细胞培养液中, 剪切至1 mm3左右, 再分散排布于含1.5 mL培养基(渗透压1100 mOsm/kg)的25 cm2培养瓶中, 置于生化培养箱中。根据预实验结果, 设定培养温度为20℃, 培养基pH 7.2~7.4, 24 h内更换培养基至2 mL, 之后每隔1~ 2 d更换培养基1次, 逐步清除培养体系中的污染物, 至1周后每隔3 d更换培养基1次, 2周后每隔1周更换培养基1次。Nikon TS100倒置显微镜下定期观察细胞迁出和生长情况并拍照记录。

1.3.4 数据的统计分析所有数据以x±SD (n≥6)表示。使用SPSS 17.0软件进行差异性分析, 以P < 0.05表示显著性差异, 以P < 0.01表示极显著差异。

2 结果与分析 2.1 基础培养基筛选3种基础培养基中, L-15培养基中扇贝心脏细胞迁出细胞数量最高, L-15+M199培养基次之, M199培养基最少。L-15培养基及L-15+M199培养基中多数迁出细胞存活2周左右, M199培养基中多数细胞存活1周左右(表 2)。

|

|

表 2 不同基础培养基中栉孔扇贝细胞存活情况比较 Tab.2 Comparison of Chlamys farreri cell migration and survival in different basic media |

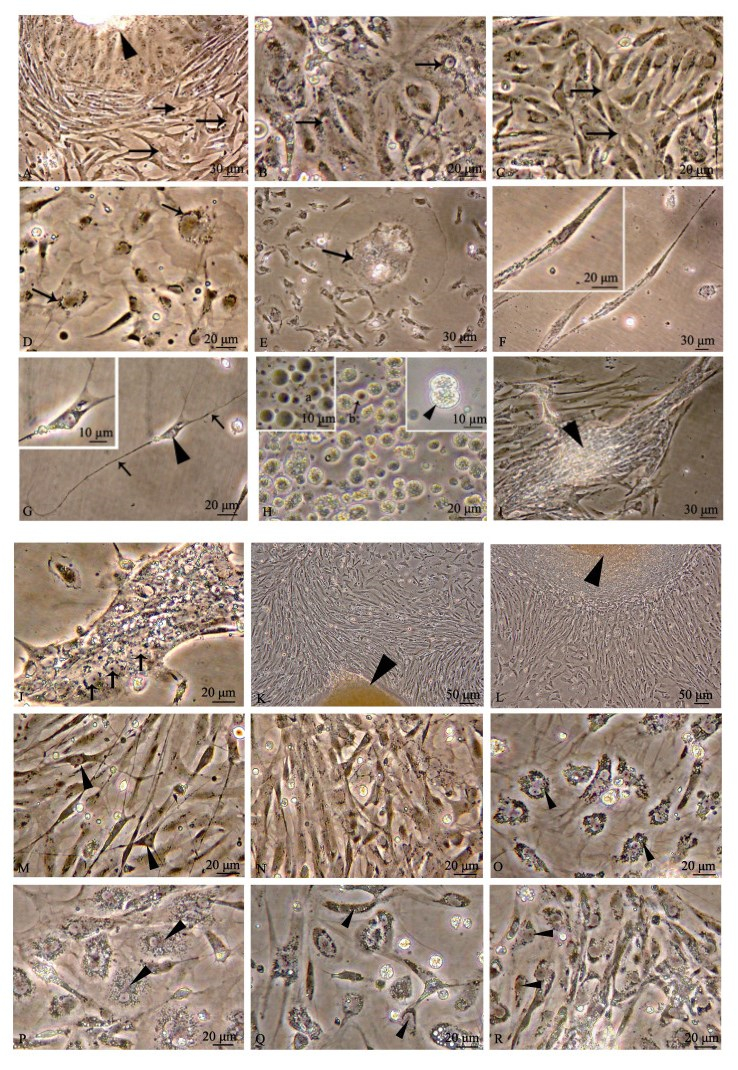

根据形态特征, 将体外培养的心脏细胞划分为6种类型。(1)心肌细胞:该类细胞大量存在, 占培养细胞的80%~90%, 其中10%~20%心肌细胞节奏性搏动, 表现为单个细胞的搏动及细胞团或细胞层的收缩。培养早期, 在显微镜下观察到单个心肌细胞收缩速率较快(32~46次/min), 随后培养速率减慢(2次/min), 收缩维持3~5 d; 细胞单层收缩可维持较长时间(1~2周), 并且始终保持高的搏动速率(50~60次/min)。心肌细胞包括2个亚型, 第1类心肌细胞由组织块中密集成簇迁出, 为成纤维状, 贴壁充分舒展后, 细胞多突起, 相邻细胞突起部分融合(图 1A、图 1C); 第2类心肌细胞由组织块中迁出后即保持单层舒展状, 细胞边界不能分辨, 核周围分布少量颗粒, 单核仁明显(图 1B), 这类心肌细胞体外存活时间最长。(2)上皮样细胞:细胞边缘呈波浪状(图 1D)。(3)不规则形大细胞:细胞体积相当于普通细胞的5~20倍(图 1E)。(4)成纤维细胞:细胞呈长梭形(图 1F)。(5)神经细胞:胞体较小, 有2~3个细长突起(图 1G)。(6)血细胞:可分为3种, 即褐色细胞(图 1H)、透明细胞(图 1H)和粒细胞(图 1H), 其中粒细胞可偶见分裂相(图 1H插图)。心脏细胞原代培养产物中, 以心肌细胞为主, 其余细胞类型少量分布, 同心肌组织细胞组成特性一致。原代培养第1~2周, 心肌细胞密集的单层处, 局部心肌细胞排列形成肌束(图 1I); 同时, 大量细胞核高密度聚集, 形成心肌组织结构的雏形——肌管(图 1J), 表明原代培养心肌细胞分化成熟。

|

图 1 体外培养的栉孔扇贝心脏细胞

A.组织块迁出细胞(第2天), ►示组织块,  示第1类多突起心肌细胞; B.第2类心肌细胞(第32天), 示第1类多突起心肌细胞; B.第2类心肌细胞(第32天),  示颗粒围绕细胞核, 单核仁明显; C.第1类多突起心肌细胞(第6天), 示颗粒围绕细胞核, 单核仁明显; C.第1类多突起心肌细胞(第6天),  示相邻细胞突起相互融合; D.上皮样细胞(第2天), 示相邻细胞突起相互融合; D.上皮样细胞(第2天),  示颗粒围绕细胞核; E.不规则形大细胞(第7天), 示颗粒围绕细胞核; E.不规则形大细胞(第7天),  示细胞颗粒; F.成纤维样细胞(第23天); G.神经细胞(第10天), ►示细胞胞体, 示细胞颗粒; F.成纤维样细胞(第23天); G.神经细胞(第10天), ►示细胞胞体,  示细胞突起; H.血细胞(第16天), a代表第1种血细胞, b代表第2种血细胞( 示细胞突起; H.血细胞(第16天), a代表第1种血细胞, b代表第2种血细胞( 示], c代表第3种颗粒性血细胞, ►示分裂末期细胞; I.心肌束(第9天), ►示心肌细胞紧密排列; J.肌管(第7天), 示], c代表第3种颗粒性血细胞, ►示分裂末期细胞; I.心肌束(第9天), ►示心肌细胞紧密排列; J.肌管(第7天),  示细胞核(a~j培养条件: L-15, 10% FBS); K.组织块迁出细胞(第2天, 培养条件5% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示组织块; L.组织块迁出细胞(第3天, 培养条件20% FBS, 20 mmol/L牛磺酸, 2 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示组织块; M.密集的细胞单层(第4天, 培养条件5% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示神经细胞; N.密集的细胞单层(第4天, 培养条件10% FBS, 5 mmol/L牛磺酸, 4 mmol/L Ca2+); O.心肌细胞(第14天, 培养条件 示细胞核(a~j培养条件: L-15, 10% FBS); K.组织块迁出细胞(第2天, 培养条件5% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示组织块; L.组织块迁出细胞(第3天, 培养条件20% FBS, 20 mmol/L牛磺酸, 2 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示组织块; M.密集的细胞单层(第4天, 培养条件5% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示神经细胞; N.密集的细胞单层(第4天, 培养条件10% FBS, 5 mmol/L牛磺酸, 4 mmol/L Ca2+); O.心肌细胞(第14天, 培养条件20% FBS, 5 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示颗粒围绕细胞核; P.心肌细胞(第17天, 培养条件20% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 4 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示颗粒围绕细胞核; Q.退化细胞(第22天, 培养条件10% FBS, 20 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), ►示细胞边缘不规则降解; r.第2类心肌细胞(第55天, 培养条件5% FBS, 50 mmol/L牛磺酸, 6 mmol/L Ca2+)如►所示. Fig.1 The cultured heart cells from Chlamys farreri in vitro A. Cells migrating from explants (2nd day); arrowhead shows explant; arrow shows cardiomyocytes with several extensions. B. The second kind of cardiomyocytes (32nd day); arrow shows granules surrounding the nuclear with single nucleolus. C. Cardiomyocytes with several extensions (6th day); arrow shows fusing of extensions from neighbouring cardiomyocytes. D. Epithelial-like cells (2nd day); arrow shows granules surrounding the nucleus. E. Irregular large cells (7th day); arrow shows granules in the cell. F. Fibroblast-like cells (23rd day). G. Neurons (10th day); arrowhead shows soma; arrow shows neurite. H. Hemocytes (16th day); a represents the first kind of hemocytes; b represents the second kind of hemocytes; c represents the third kind of hemocytes filled with granules; arrowhead shows cell at telophase. I. The bunch of cardiomyocytes (9th day); arrowhead shows close arrangement of cardiomyocytes. J. Myotube (7th day); arrow shows nucleus. A~J culture condition in a~j: L-15, 10% FBS. K. Cell migrating from explant (2nd day, culture condition: 5% FBS, 50 mmol/L taurine, 6 mmol/L Ca2+); arrowhead shows explant; L. cell migrating from explant (3rd day, culture condition: 20% FBS, 20 mmol/L taurine, 2 mmol/L Ca2+); arrowhead shows explant. M. Dense cell layer around the explant (4th day, culture condition: 5% FBS, 50 mmol/L taurine, 6 mmol/L Ca2+); arrowhead shows neurons. N. Dense cell layer around the explant (4th day, culture condition: 10% FBS, 5 mmol/L taurine, 4 mmol/L Ca2+). O. Cardiomyocytes (14th day, culture condition: 20% FBS, 5 mmol/L taurine, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), arrowhead shows granule around the nucleus. P. Cardiomyocytes (17th day, culture condition: 20% FBS, 50 mmol/L taurine, 4 mmol/L Ca2+); arrowhead shows granule around the nuclear. Q. Degenerated cell (22nd day, culture condition: 10% FBS, 20 mmol/L taurine, 6 mmol/L Ca2+); arrowhead shows irregular degradation along cell edge. R. The second kind of cardiomyocyte (55th day, culture condition: 5% FBS, 50 mmol/L taurine, 6 mmol/L Ca2+), as arrowhead shown. |

培养起始24 h后, 各组组织块逐步迁出单细胞; 培养第3天, 组织块迁出最旺盛(图 1K、图 1L), 在组织块周围迁出大量的细胞(图 1M、图 1N)。表 3为培养第3天各组平均细胞迁出距离及最大细胞迁移距离。

|

|

表 3 添加物浓度筛选 Tab.3 Option of the concentration of additives |

正交实验结果显示, 随着胎牛血清浓度的升高, 心脏植块中的细胞平均迁出距离及最大迁出距离均呈现下降趋势, 即: 5% FBS实验组(表 3, 组1~组3)细胞迁出距离最远, 10% FBS(表 3, 组4~组6)次之, 20% FBS(表 3, 组7~组9)最近; 同一胎牛血清浓度下, 不同浓度的牛磺酸及Ca2+对组织块迁出没有规律性影响(表 3)。差异显著性分析结果显示, 含有5% FBS的组1~组3的培养基中细胞平均迁移距离均显著高于含有20% FBS的组7~组9, 其中以组3培养基的细胞迁出效果最佳。

2.3.2 各培养条件下细胞存活时间比较20% FBS各组(表 3组7~组9)细胞最早发生退化, 2周后大量细胞消失。组7、组8中残存的心肌细胞同早期相比细胞体积增大2倍左右, 胞质中分布大量颗粒密集围绕核区(图 1O); 组9残存的心肌细胞, 同组7、组8相比, 颗粒小但更加密集存在于胞质中(图 1P)。组7~组9残存细胞培养25~30 d后退化死亡。

5% FBS各组(表 3组1~组3)、10% FBS各组(表 3组4~组6)培养3周后大量细胞开始退化, 退化细胞多呈现细胞边缘不规则降解(图 1Q)。5% FBS中组1、组2及10% FBS各组(表 3组4~组6)细胞存活20~30 d。组3(5% FBS、50 mmol/L牛磺酸、6 mmol/L Ca2+)中第2类心肌细胞体外存活达60 d (图 1R)。

3 讨论 3.1 双壳类心脏细胞培养特点已有研究表明, 双壳类心肌组织原代培养物主要包括3种类型细胞, 即圆形细胞、上皮样细胞和成纤维样细胞。其中成纤维样细胞是主要的细胞类型, 超微结构及肌球蛋白免疫组化检测确定成纤维样细胞为心肌细胞; 这些心肌细胞通常具备一定的功能活力, 且少数能够自发地节奏性搏动, 细胞单层处形成类似肌管样结构[4, 7, 12, 14]。本研究发现在栉孔扇贝心肌植块细胞培养中, 细胞成簇旺盛迁出, 通过心肌搏动确定多数细胞为心肌细胞, 此外还有少量存在的上皮样细胞、成纤维样细胞、神经细胞、血细胞(图 1A~图 1H)。在多层迁出细胞处, 表层的细胞可维持1~2周有节奏地搏动, 此现象在太平洋牡蛎(C. gigas)的心脏细胞原代培养中也见报道[13]; 在细胞单层处, 可见类似心肌束、肌管样结构, 表明本实验原代培养的心肌细胞已分化成熟。

3.2 双壳类心脏细胞培养条件海洋无脊椎动物细胞培养大多采用脊椎动物商业化的培养基, 添加多种无机盐以提高渗透压。双壳类心脏细胞培养中的一个重点是对各种商业合成培养基进行筛选。Wen等[4]比较了6种合成培养基(F10、NCTC-135、RPMI1640、MEM、M199、L-15)对丽文蛤(Meretrix lusoria)心脏组织的培养效果, 以L-15和M199培养基中组织块迁出细胞数量最多; 且在L-15培养基中组织块释放细胞数量及维持细胞存活较M199培养基更优。在欧洲扇贝(P. maximus)的心脏细胞培养中, Le Marrec-Croq等[13]将细胞培养在溶于海水的L-15培养基中, 可使其体外维持1个月左右。本研究中, L-15培养基更利于细胞从组织块中迁出和存活, L-15培养基同M199培养基混合次之, M199培养基最差。由上述实验结果, 可以初步推断, 双壳类心脏细胞在含有高浓度氨基酸的培养基(如L-15)中较碳酸氢钠缓冲系统的培养基中更容易获得培养物。

血清是细胞培养中最常用的添加物, 含有各种促生长因子、激素、促贴壁物质、微量元素以及矿物质, 对细胞生长和增殖至关重要。在双壳类外套膜、消化腺、心脏、鳃等组织培养中, 绝大多数采用10% FBS, 5% FBS或20% FBS较少使用[14, 18-21]。本研究选择3个FBS浓度5%、10%和20%, 分别添加到L-15培养基中, 结果显示, 低浓度血清(5% FBS)更利于细胞从组织块中迁出, 细胞存活时间也最长。

牛磺酸是哺乳动物心肌组织中最丰富的游离氨基酸, 参与多个重要的生理调节活动, 比如, 可调节渗透压及离子运输, 稳定细胞内Ca2+水平[22-23]; 可维持心肌正常结构及功能, 敲除牛磺酸运输基因将导致心肌萎缩及心肌症[24]; 可抑制缺血-再灌注损伤、药物处理、Ca2+超载、去钾肾上腺素处理等心肌损伤导致的心肌细胞凋亡[25-28]。在哺乳动物中, 张晓敏等[29]发现牛磺酸对培养乳鼠心肌细胞的缺氧坏死起到保护作用。海洋双壳类血淋巴含有丰富的牛磺酸[17], 而L-15培养基中缺少该成分。本研究添加牛磺酸后, 可显著延长心脏细胞的存活时间, 且在5% FBS、50 mmol/L牛磺酸条件下, 细胞存活长达60 d。类似的实验结果在合浦珠母贝(Pinctada fucata)外套膜组织培养中也有报道[28]。尽管在双壳类心肌细胞培养中一般需要添加Ca2+(多为6 mmol/L)[5-7], 哺乳动物心肌细胞培养中Ca2+浓度常维持在1.8 mmol/L[30], 但本研究中各Ca2+浓度组(2 mmol/L、4 mmol/L、6 mmol/L)对栉孔扇贝心脏细胞培养效果的影响未见明显差别。这可能与本研究中添加了牛磺酸有关, 牛磺酸可调节细胞内Ca2+至适宜的水平, 由此导致添加额外的Ca2+未见明显的改善效果[31]。

本研究通过对栉孔扇贝心脏细胞体外培养的基础培养基和培养基添加物的筛选, 初步确定了栉孔扇贝心脏细胞适宜培养基为L-15中基础培养基中添加5% FBS、50 mmol/L牛磺酸及6 mmol/L Ca2+。在该培养基中, 心脏细胞体外存活可达2个月之久, 实现了栉孔扇贝心脏细胞体外培养。

| [1] |

Cai X, Zhang Y. Marine invertebrate cell culture:a decade of development[J]. Journal of Oceanography, 2014, 70(5): 405-414. DOI:10.1007/s10872-014-0242-8 |

| [2] |

Yoshino T P, Bickham U, Bayne C J. Molluscan cells in culture:primary cell cultures and cell lines[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2013, 91(6): 391-404. DOI:10.1139/cjz-2012-0258 |

| [3] |

Li J J, Huang B Y. Technology and application of marine shellfish cell culture[J]. Marine Science Bulletin, 2015(3): 247-251. [李建军, 黄宝玉. 海洋贝类细胞培养技术及其应用[J]. 海洋通报, 2015(3): 247-251.] |

| [4] |

Wen C M, Kou G H, Chen S N. Cultivation of cells from the heart of the hard clam, Meretrix lusoria, (Röding)[J]. Methods in Cell Science, 1993, 15(3): 123-130. |

| [5] |

Domart-Coulon I, Doumenc D, Auzoux-Bordenave S, et al. Identification of media supplements that improve the viability of primarily cell cultures of Crassostrea gigas oysters[J]. Cytotechnology, 1994, 16(2): 109-120. DOI:10.1007/BF00754613 |

| [6] |

Renault T, Flaujac G, Le Deuff R M. Isolation and culture of heart cells from the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis[J]. Methods in Cell Science, 1995, 17(3): 199-205. DOI:10.1007/BF00996127 |

| [7] |

Chen S N, Wang C S. Establishment of cell lines derived from oyster, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg and hard clam, Meretrix lusoria Röding[J]. Methods in Cell Science, 1999, 21(4): 183-192. |

| [8] |

Rinkevich B. Marine invertebrate cell cultures:new millennium trends[J]. Marine Biotechnology, 2005, 7(5): 429-439. DOI:10.1007/s10126-004-0108-y |

| [9] |

Domart-Coulon I, Auzoux-Bordenave S, Doumenc D, et al. Cytotoxicity assessment of antibiofouling compounds and by-products in marine bivalve cell cultures[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2000, 14(3): 245-251. DOI:10.1016/S0887-2333(00)00011-4 |

| [10] |

Hanana H, Talarmin H, Pennec J P, et al. Establishment of functional primary cultures of heart cells from the clam Ruditapes decussatus[J]. Cytotechnology, 2011, 63(3): 295-305. DOI:10.1007/s10616-011-9347-8 |

| [11] |

Deuff R M L, Lipart C, Renault T. Primary culture of Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, heart cells[J]. Methods in Cell Science, 1994, 16(1): 67-72. |

| [12] |

Pennec J P, Gallet M, Gioux M, et al. Cell culture of bivalves:tool for the study of the effects of environmental stressors[J]. Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2002, 48(4): 351-358. |

| [13] |

Le Marrec-Croq F, Glaise D, Guguen-Guillouzo C, et al. Primary cultures of heart cells from the scallop Pecten maximus (mollusca-bivalvia)[J]. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology-Animal, 1999, 35(5): 289-295. DOI:10.1007/s11626-999-0073-x |

| [14] |

Lang G H, Wang Y, Liu W S, et al. Study on primary culture of Chlamys farreri mantle cells[J]. Journal of Ocean University of Qingdao, 2000, 30(1): 123-126. [郎刚华, 王勇, 刘万顺, 等. 栉孔扇贝(Chlamys farreri)外套膜组织原代培养的初步研究[J]. 青岛海洋大学学报, 2000, 30(1): 123-126. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-5174.2000.01.014] |

| [15] |

Lin N. A primary study on cell culture of testis from the scallop Chlamys farreri[D]. Qingdao: Ocean University of China, 2011. [林娜.栉孔扇贝(Chlamys farreri)精巢细胞体外培养的初步研究[D].青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2011.] http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10423-1011228863.htm

|

| [16] |

Yan M. Establishment and characteristic analysis of larval and tissue cells in vitro in Chlamys farreri[D]. Qingdao: Ocean University of China, 2013. [晏萌.栉孔扇贝(Chlamys farreri)幼虫和成体组织细胞的体外培养体系建立和特征分析[D].青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2013.] http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10423-1013354661.htm

|

| [17] |

Gong N P, Ma Z J, Li Q, et al. Characterization of calcium deposition and shell matrix protein secretion in primary mantle tissue culture from the marine pearl oyster Pinctada fucata[J]. Marine Biotechnology, 2008, 10(4): 457-465. DOI:10.1007/s10126-008-9081-1 |

| [18] |

Birmelin C, Pipe R K, Goldfarb P S, et al. Primary cell-culture of the digestive gland of the marine mussel Mytilus edulis:a time-course study of antioxidant-and biotransformation-enzyme activity and ultrastructural changes[J]. Marine Biology, 1999, 135(1): 65-75. |

| [19] |

Gómez-Mendikute A, Elizondo M, Venier P, et al. Characterization of mussel gill cells in vivo and in vitro[J]. Cell and Tissue Research, 2005, 321(1): 131-140. DOI:10.1007/s00441-005-1093-9 |

| [20] |

Cornet M. Primary mantle tissue culture from the bivalve mollusc Mytilus galloprovincialis:investigations on the growth promoting activity of the serum used for medium supplementation[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2006, 123(1): 78-84. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.10.016 |

| [21] |

Suja C P, Sukumaran N, Dharmaraj S. Effect of culture media and tissue extracts in the mantle explant culture of abalone, Haliotis varia Linnaeus[J]. Aquaculture, 2007, 271(1-4): 516-522. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.04.086 |

| [22] |

Huxtable R J. Physiological actions of taurine[J]. Physiological Reviews, 1992, 72(1): 101-163. DOI:10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101 |

| [23] |

Satoh H, Sperelakis N. Review of some actions of taurine on ion channels of cardiac muscle cells and others[J]. General Pharmacology:The Vascular System, 1998, 30(4): 451-463. DOI:10.1016/S0306-3623(97)00309-1 |

| [24] |

Ito T, Kimura Y, Uozumi Y, et al. Taurine depletion caused by knocking out the taurine transporter gene leads to cardiomyopathy with cardiac atrophy[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2008, 44(5): 927-937. DOI:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.001 |

| [25] |

Mohamed H E, Asker M E, Ali S I, et al. Protection against doxorubicin cardiomyopathy in rats:role of phosphodiesterase inhibitors type 4[J]. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 2004, 56(6): 757-768. DOI:10.1211/0022357023565 |

| [26] |

Oriyanhan W, Yamazaki K, Miwa S, et al. Taurine prevents myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in prolonged hypothermic rat heart preservation[J]. Heart and Vessels, 2005, 20(6): 278-285. DOI:10.1007/s00380-005-0841-9 |

| [27] |

Xu Y J, Saini H K, Zhang M, et al. MAPK activation and apoptotic alterations in hearts subjected to calcium paradox are attenuated by taurine[J]. Cardiovascular Research, 2006, 72(1): 163-174. |

| [28] |

Li Y, Arnold J M O, Pampillo M, et al. Taurine prevents cardiomyocyte death by inhibiting NADPH oxidase-mediated calpain activation[J]. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2009, 46(1): 51-61. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.025 |

| [29] |

Zhang X M, Zhou Q Y. Protective effects of taurine on myocardial necrosis induced by hypoxia in vitro[J]. Anthology of Medicine, 2001, 20(6): 760-762. [张晓敏, 周巧云. 牛磺酸对培养乳鼠心肌细胞缺氧坏死的保护作用[J]. 医学文选, 2001, 20(6): 760-762. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-6575.2001.06.003] |

| [30] |

Wang T H, Wu B, Zhu X N, et al. Effects of endothelin on intracellular free calcium concentration in cultured cardiom-yocytes[J]. Journal of Physiology, 1999, 51(4): 391-396. [王庭槐, 吴滨, 朱小南, 等. 内皮素对培养心肌细胞内游离钙浓度的作用[J]. 生理学报, 1999, 51(4): 391-396. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0371-0874.1999.04.005] |

| [31] |

Bkaily G, Jaalouk D, Sader S, et al. Taurine indirectly increases[Ca]i by inducing Ca2+ influx through the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 1998, 188: 187-197. DOI:10.1023/A:1006806925739 |

2018, Vol. 25

2018, Vol. 25